The Case for Markup Languages for Typesetting

Markup and Typesetting

Typesetting is the process of specifying the details of how a written document is represented visually, from the margins’ widths and the page size, to the font choice, style, and spacing.

In the days of the printing press, a publisher would read through a written document and add notes in the margin on how the document was to be printed. The typesetter would then follow these notes — the Markup — to set the physical type and generate the final printed document.

This process, Markup and Typesetting, is still how all modern-day software generates written documents. While popular word processing software like Microsoft Word hide the mechanics from the user, underneath the hood, every bolded word and indented paragraph is specified by a Markup language that tells the software how to represent the document onscreen or a printer how to render it.

WYSIWYG vs WYSIWYM

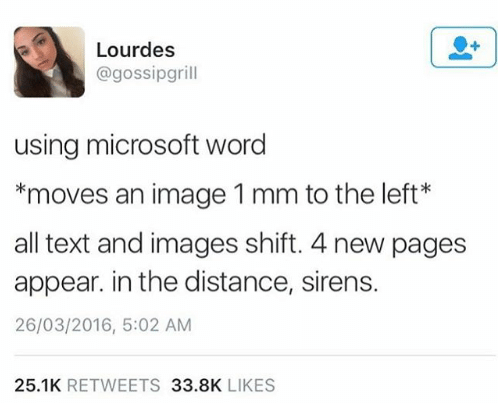

For most day to day purposes, word processors like Microsoft Word are fast and convenient. However, if you’ve ever written a long document (e.g: over 100 pages), or one with complex structure (chapters or nested subsections) or embedded images, you may have found the convenience quickly gives way to frustration and chaos.

Microsoft Word is what is known as a WYSIWYG (What You See is What You Get). The tradeoff for the speed and convenience of real-time typesetting is a sometimes inexplicable and often infuriating lack of control of how the document is formatted.

The alternative to the WYSIWYG is a WYSIWYM (What You See I What You Meant). A WYSIWYM usually requires the user to annotate their document as they write with a specific Markup language, then pass the document through some form of interpreter in order to generate the final document. While this process sacrifices the readability of real-time typesetting, and requires a certain degree of proficiency with the markup language of choice, a WYSIWYM (in theory) provides the user complete control over every aspect of the final document.

Common Markup Languages

html

The most popular Markup language in the world is probably html, which is used to determine how nearly all text on the web is rendered. For a sense of how html markup looks, try right-clicking on this page and selecting View Page Source. Each one of those colons, quotes, and parentheses provides typesetting instructions for your browser. The browser then consults the page’s associated Cascading Style Sheet (CSS) on how each markup instruction should be rendered onscreen. Two different CSS style sheets will generate two different web pages (e.g: different layout, text sizes, or colors).

LaTeX

and its progenitor

(pronounced “laytech” and “tech”, the last letter is a Greek Chi, not an ‘x’) are part of a family of WYSIWYM languages originally developed for typesetting printed documents that is still widely used for typesetting books, journal articles, and theses. Like, html, user annotates a written document with specific markup tags then passes it through a

interpreter that renders the final document based on the Class and packages specified by the user. While it has a steep learning curve and can be intimidating for the novice user, it is an extremely powerful tool with a large (if diminishing) user base. If you’re interested in trying your hand at

, start with our tutorial here.

Markdown

Markdown is the youngest and simplest of common markup languages. Variations of it are used in many websites and applications, such as reddit, Wordpress, Slack, and WhatsApp. If you’ve ever bolded text with a couple of asterisks, you’ve used Markdown.

The Simplicity of Markdown

The beauty and power of Markdown lie in its simplicity. It is easy to write and easy to read.

Compare, for example, some common markup tags between html, , and their Markdown equivalents:

| Markup | html |

|---|---|

| Section Heading | <h1 id=”your-section”>Your Section<\/h1> |

| Subsection Heading 1 | <h2 id=”your-section-1”>Your Section<\/h2> |

| Subsection Heading 2 | <h3 id=”your-section-2”>Your Section<\/h3> |

| Bold Text | <p><em>Bold<\/em><\/p> |

| Italicized Text | <p><em>italics<\/em><\/p> |

| Bold italics | <p><em><em>bold italics<\/em><\/em><\/p> |

| Superscripts | <p>10<sup>5<\/sup><\/p> |

| Subscripts | <p>H<sub>2<\/sub>O<\/p> |

Table 1. Common html markup tags.

| Markup | |

|---|---|

| Section Heading 1 | \section{Your Section}\label{your-section} |

| Section Heading 2 | \subsection{Your Section}\label{your-section-1} |

| Section Heading 3 | \subsubsection{Your Section}\label{your-section-2} |

| Bold Text | \emph{Bold} |

| Italicized Text | \emph{italics} |

| Bold italics | \emph{\emph{bold italics}} |

| Superscripts | 10\textsuperscript{5} |

| Subscripts | H\textsubscript{2}O |

Table 2. Common  markup tags.

| Markup | Markdown |

|---|---|

| Section Heading 1 | # Your Section |

| Section Heading 2 | ## Your Section |

| Section Heading 3 | ### Your Section |

| Bold Text | *Bold* |

| Italicized Text | _italics_ |

| Bold italics | *_bold italics_* |

| Superscripts | 10\^5\^ |

| Subscripts | H~2~O |

Table 3. Common Markdown markup tags.

Compared to the other two, Markdown is much more intuitive and much less disruptive to read and write. More importantly, however, translators such as pandoc (see below) allow you to write in Markdown then convert your document. So, if you need to write text for a webpage, or want to try with training wheels, Markdown + pandoc is for you.

An Introduction to pandoc

Pandoc: a universal markup interconversion tool

Regardless of what writing software or markup language you prefer, there will come a time when obstinate collaborators or strict document submission guidelines will force you to change the format of your document. Enter pandoc.

pandoc is a (near) universal markup translator. Since every word processing format has a markup language at its core, converting from one to another is just a matter of replacing one language’s markup for another. If you have a complex, thousand page document written in , and need to convert it to Microsoft Word, a single pandoc command will do most of the work.

Installing pandoc and other useful tools

Guidelines for installing pandoc on various operating systems can be found here.

To get the most out of the rest of this demo, I recommend using a plain text editor with good syntax highlighting support, such as Atom or Sublime Text. Activating the Markdown syntax highlighting in either of these programs will be helpful (see here for Atom, or here for Sublime Text).

For the more advanced examples below, you’ll need to install one of the many available

distributions. I recommend MikTeX.

Lastly, this demo assumes a certain degree of familiarity with a *\nix command line and the bash shell. If you don’t know how to change directories and call programs from the command line, you may wish to familiarize yourself with these basics before proceeding.

Your first pandoc conversion

Save this sample_markdown_file.md in your working directory. Open it with the text editor of your choice and take a look. You should see a few paragraphs of text marked up with common Markdown markups (e.g. #, *, etc).

Let’s try converting it to a pdf with pandoc. Type the following into the command line:

pandoc sample_markdown_file.md -o example_01.pdf

Open the example_01.pdf and take a look. You see a nicely rendered document with nested heading levels. All the markup is gone. What pandoc just did was take the Markdown file, translate the Markdown markup into , then render the

as a pdf.

If you wanted to stop at the intermediate, you can. Try this on the command line:

pandoc sample_markdown_file.md -o example_02.tex

If you open example_02.tex with your text editor, you should the same text as the Mardown file, except extensively marked-up with .

Converting to Microsoft Word from Markdown

pandoc can also convert Markdown markup to MS Word markup. Try directly converting the sample_markdown_file.md to a .docx file by entering the following into the command line.

pandoc sample_markdown_file.md -o example_03.docx

Open example_03.docx in MS Word and take a look. You should see the document rendered into the default settings of your MS Word.

If the default settings aren’t to your liking, you can always use a different document (.docx) or template (.dotx) for conversion.

For example, download msword1.dotx into your working directory. Open the file in Word and take a look. You should see an abbreviated article style after the BECL website. If we use this document as a reference, we can convert our Markdown file into that same style.

Try running the following on the command line:

pandoc sample_markdown_file.md --reference-doc msword1.dotx -o example_04.docx

Open example_04.docx and take a look. The sample_markdown_file.md should now be in the style as msword1.dotx.

This will work for any pre-generated MS Word style template or document. Try it again. Download msword2.dotx into your working directory. Open it up in Word and take a look. This time, the file should appear blank. However, the style information is still encoded. Try converting your Markdown file with msword2.dotx as a reference:

pandoc sample_markdown_file.md --reference-doc msword2.dotx -o example_05.docx

Open example_05.docx using MS Word. See the difference in formatting?

Try it again with any MS Word file of your own on your computer. pandoc should convert the Markdown file such that the final output matches the reference document’s style.

Putting LaTeX in your Markdown

Symbols

Symbols

has long been the language of choice for writing out complex math equations. You can find a list of

commands for different math and scientific symbols here. Pandoc will recognize and render

symbols within markdown if you surround them with dollar signs.

Open up the sample_markdown_file.md in your text editor and try adding some of the following symbols in different places:

$\mu$

$\pi$

$\phi$

$\infty$

$\leq$

$\neq$

Save your edited file and convert it to pdf:

pandoc sample_markdown_file.md -o example_06.pdf

Open the example_06.pdf and see how they rendered.

inline Typesetting

inline Typesetting

Since pandoc converts markdown to pdf by way of , you can include direct

code in your markdown document.

For example, try adding this unassuming command somewhere in sample_markdown_file.md.

\LaTeX

Save the file, and try converting to pdf:

pandoc sample_markdown_file.md -o example_07.pdf

If everything worked, you should see the stylized, offset rendering of instead of the mixed case LaTeX you typed in.

The ability to embed commands within your Markdown document can provide added control over the layout of your document. Try adding the following command after the first section in the sample_markdown_file.md:

\pagebreak

Save the file, and convert to pdf:

pandoc sample_markdown_file.md -o example_08.pdf

Open up example_08.pdf and take a look. You should see the page ends exactly where you pasted the command and begins again on the next page.

Changing Class Options with YAML

Every document has an associated class (e.g. Book, Thesis, Letter, Article), and every document class is defined by a set of defaults settings (e.g. font, font size, margins, etc) that can be adjusted and customized by the user. Normally, a

document will begin with a preamble that specifies these settings.

These same class features and settings can be specified in a Markdown document prior to pandoc conversion using a YAML (“Yet Another Markup Language”) block.

Try adding the following to the very beginning of the sample_markdown_file.md:

---

mainfont: Helvetica

fontsize: 12pt

urlcolor: cyan

---

Save the file and convert it to pdf. Note that this time we are calling a specific engine (xelatex) to perform the conversion.

pandoc sample_markdown_file.md --pdf-engine=xelatex -o example_09.pdf

Open example_09.pdf and take a look. Can you see the changes? Open sample_markdown_file.md again, but make the following changes:

---

mainfont: Courier New

fontsize: 10pt

urlcolor: red

---

Save and convert it into a pdf:

pandoc sample_markdown_file.md --pdf-engine=xelatex -o example_10.pdf

Open example_10.pdf and take a look.

The pandoc Markdown to conversion allows you to adjust nearly any setting you can change in

by specifying it in the YAML, including calling and loading

packages. For further documentation, including the default settings, see here.

References and Citations

If you’re using Markdown for academic writing, you can easily pass citations through pandoc with the pandoc-citeproc package. To install pandoc-citeproc, you’ll need to use the Homebrew manager.

brew install pandoc pandoc-citeproc

Most commonly used reference management software packages will generate compatible bibliographies. For this example, I used Zotero with the BetterBibTeX. Zotero and BibTeX convert your reference list into a

readable bibliography file and provide a unique key for you to call in text.

Try pasting the following at the end of the sample_markdown_file.md and saving it:

### Recommended Reading

Two important early texts on the theory of data visualization were Edward Tufte's seminal work, _The_ _Visual_ _Display_ _of_ _Quantitative_ _Information_ [@tufteVisualDisplayQuantitative2015] and William S. Cleveland's _Visualizing_ _Data_ [@clevelandVisualizingData1993]. Leland Wilkinson's _Grammar_ _of_ _Graphics_ [@wilkinsonGrammarGraphics2012] was the first work to establish a comprehensive nomenclature for data visualization. The **BE** **Communication** **Lab** recommends Jean-Luc Dumont's _Trees,_ _Maps,_ _and_ _Theorums_ [@doumontTreesMapsTheorems2009] as an introductory text on data visualization and communication.

$\newpage$

## Works Cited

See the reference keys starting with the square parentheses and \@ symbols? They are stand-ins for how the citation in the Markdown text. When converting through pandoc, we will specify a citation style and the final document will be rendered in that style.

Download this bibliography file, pandoc_demo.bib, and this citation style file (from the journal, Cell), cell.csl, into your working directory. Now, convert it to a pdf while calling the bibliography and citation style:

pandoc sample_markdown_file.md --filter pandoc-citeproc --bibliography=pandoc_demo.bib --csl=cell.csl -o example_11.pdf

Open up example_11.pdf and scroll to the end and take a look. You should see the citation keys replaced by the author names and years, and a final reference list, all conforming to the Cell style guidelines.

You can find style files for other journals here. Try downloading the .csl file of your favorite journal using it in the place of the cell.csl.

You can even use this method to generate an MS Word file with full citations:

pandoc sample_markdown_file.md --filter pandoc-citeproc --bibliography=pandoc_demo.bib --csl=cell.csl -o example_12.docx